Navigation

Midterm Questions 1 | 2Final Assignments Wiki | Thematic | Creative | Clybourne

Bitter Cane by Genny Lim

Bitter Cane centers on Hawaii's complicated history of Chinese laborers contracted to work in the Hawaiian sugarcane fields during the late 1800s. It paints a seemingly hopeless narrative of the exploitation of Chinese laborers and the oppressive institutions of Chinese women through the stories of Wing Chung Kuo and Li-Tai. Haunted by his father's disgrace to their family, sixteen-year-old Wing leaves for Hawaii to search for a better life and his own identity. Li-Tai is a Chinese woman on the plantation who desires to escape from her life of physical and spiritual bondage, trapped by prostitution and opium addiction.

It is impossible for me to engage in the spirit and emotion of an ethnic play without identifying myself in some way with the female character because of how my life experiences have been informed by my own identity as a Asian American female. In this play, I imagine myself portraying the character of Li-Tai. Though she was oppressed and subjugated in nearly every aspect of her life since childhood, from bound feet to bound soul, Li-Tai's character challenges the cultural and sexual stereotypes of Chinese women during that time.

To prepare for this role I would research bound feet to attempt to understand its influence on Li-Tai's physical movements and emotions. For Li-Tai and other Chinese women before the 20th century, foot binding restricted the mobility of women. Foot binding in China was not only a common practice for displaying status for wealthy women, but it was also used as a means for poor girls to be able to marry into money. It is also an important symbol within the narrative and Li-Tai's character because bound feet were considered erotic to men in Chinese culture. In the play, Kam is aroused by Li-Tai's struggling with her bound feet and calls her a "crippled woman" with "only petals for toes" (167).

To prepare for this role I would research bound feet to attempt to understand its influence on Li-Tai's physical movements and emotions. For Li-Tai and other Chinese women before the 20th century, foot binding restricted the mobility of women. Foot binding in China was not only a common practice for displaying status for wealthy women, but it was also used as a means for poor girls to be able to marry into money. It is also an important symbol within the narrative and Li-Tai's character because bound feet were considered erotic to men in Chinese culture. In the play, Kam is aroused by Li-Tai's struggling with her bound feet and calls her a "crippled woman" with "only petals for toes" (167).

What excites me about this play are the synchronous cultures interacting within the story. Bitter Cane incorporates a mixture of Chinese, Hawaiian, and American elements, and everything "in between" those elements. For example, Genny Lim uses themes of filial piety and words in Hawaiian Pidgin English such as "pake," which refers to a Chinese person or stingy individual. By allowing these different cultural elements to interact within the play, in some instances without definition or explanation, Lim presents a more realistic picture of Hawaii that is reflective of the complex cultural history and relationships during that time.

Back to Top

The Dance and the Railroad by David Henry Hwang

David Henry Hwang's The Dance and the Railroad tells the story of Lone and Ma, two Chinese transcontinental railroad laborers in 1867. Ma is a nosy and ambitious eighteen year old who finds Lone practicing dance and opera on a mountaintop. New to laying tracks, Ma believes the illusions that "Gold Mountain" will make him wealthy, and allow him to return to China and be a performer with twenty wives. Lone humorously scoffs at Ma's naiveté, having labored at the tracks for two years already. Though he trained in opera for eight years in China, Lone was forced by his family to abandon his craft for this brutal labor in their economic desperation. The play uses the two characters' interactions with one another to reflect the white oppression of the Chinese in building the American transcontinental railroad in the mid 1800s.

Immediately, I noticed Hwang's use of the term "ChinaMan" in the play. Rather than use any other term, Ma uses "ChinaMan" to describe himself and the other Chinese workers. In contrast, Lone does not use the word to describe himself, but only to describe the other men, isolating himself from the rest of the group. It is perplexing that Ma calls himself the same name that the "white devils" call him clearly with offensive intent. However, Hwang simultaneously suggests that he is satirizing the use of the term. In fact, he reverses the derogatory meaning and use of the word through the character of Lone, who sees the reality of their exploitation. He calls the other men "dead men" because they are succumbing to the "white devils," and he refuses to relinquish his power over his muscles. Lone's character counters the stereotypical portrayals of Chinese as submissive "coolies."

I could imagine portraying Lone in this play because I find his passion and strong spirit fascinating. In the Second Lesson: Memory of Emotion, "I" explains to Creature the notion of "unconscious memory of feeling" through a story about a married couple and the significance of cucumbers in their love story. Every time they see cucumbers they are caught by the memory of the emotions that they experienced together with the cucumber patch many years ago. "I" argues that many such memories of feeling that are waiting to be "awakened" within every artist. I think this would be a method that I use to prepare for this role. Perhaps being an artist depends on drawing upon such experiences and allowing them to flow into the role that you are portraying.

Back to Top

Back to Top

The Music Lessons by Wakako Yamauchi

When I write these stories they're really about very ordinary people. I think it's important because I'm an ordinary person. There's a lot of us doing ordinary things and yet there is courage in our lives. -Wakako YamauchiThe Music Lessons centers on the Sakata family a Japanese American farming family living in Imperial Valley, California during the late Great Depression. Chizuko Sakata is a 38-year-old widow struggling to support her daughter Aki and her two sons Ichiro and Tomu. Hardship of labor and life has left her nearly an empty shell, toiling for her and her family's subsistence. The Sakata family's life is turned upside down when 33-year old Kaoru Kawaguchi enters their lives with his suitcase and violin. As he works for Chizuko on the farm, he begins to settle down with the family and soon starts giving young Aki violin lessons, winning over her heart and awakening her sexuality. This play interweaves the reverberating stories of harsh challenges and generational conflicts faced by Japanese in America during this period.

Though her callowness towards her mother's profound sacrifices and suffering irks me, I could imagine myself portraying Aki because she reminds me of myself when I was fifteen. Growing up, though I observed my mother's physical and emotional isolation caused by a full-time job and family pressure, like Aki I could not perceive my mother's true sensibilities outside of myself. To prepare for this role, I would have to draw back on those experiences and feelings of wanting to live a different life than my mom. Since Aki likely saw Kaoru not only as a love interest, but also an escape from her difficult life, I would have to "become" someone who desperately seeks a new identity.

|

| Definition from Wikipedia. |

The Music Lessons posits that acting Asian American is fluid but also defined; it shows changing roles with second generation Japanese Americans shattering the sense of filial piety, but also demonstrates how the older generation and younger generation have their own distinctive struggles that are at odds with each other. This counters the prevailing, imagined idea that Asians and Asian Americans are the singular, silent minority. The relationship between Chizuko and Aki spotlights the distinct generational groups that emerged within the Japanese American community during the first half of the 1900s. The Gentleman's Agreement of 1907, which informally only permitted wives and children of Japanese immigrants already in the U.S. to immigrate, propelled the practice of “picture bride” marriages, where women were arranged to marry immigrant male workers through exchanging photographs. Immigrating to the U.S. as a picture bride in 1919, Chizuko was an Issei immigrant, or "first generation" Japanese in America. This group was distinct from subsequent Japanese American generations because the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Asian Exclusion Act, suppressed the U.S. immigration of Japanese until the 1940s. Her children, who were born in the United States are part of the Nisei "second generation."

The Romance of Magno Rubio by Lonnie Carter

The Romance of Magno Rubio depicts the story of a group of Pilipino male farm workers in California during the times of the Great Depression. Described as "four feet six inches tall" and "dark as a coconut ball," the main character Magno Rubio is head over heels for his antithesis Clarabelle, a 194-pound, six-feet tall blonde woman from Arkansas. He labors every day in the fields with his four friends, eagerly picking vegetables for a meager salary to send Clarabelle gifts and money. Obvious to nearly everyone except Magno Rubio, Clarabelle is a golddigger duping him out of his money. Magno Rubio's foolish pining lifts the mood of his friends as the subject of their rousing rhymes. The humor starkly contrasts with the backbreaking reality of Filipino agricultural labor in American history.

Initially the play was difficult for me to read. It irked me as an Asian American that the play contains quasi-classic Hollywood stereotypes of the Asian male, depicting characters as lecherous and lowbrow. However I realized that if anything, this play reveals important stories and actual perceptions of the early Pilipino single, male migrants in America. The reviews on the back of the book describe the play as a "tall tale" and "fable." It is true, this play is almost unbelievable with Magno Rubio being able to spend hundreds of dollars on various gifts for Clarabelle when he earns only $2.50 per day. The exaggerative elements complemented with the artful blend of music, rhyme, and the Filipino language in the dialogue, actually squelches the stereotypes and emphasizes the characters' persistence and strength during extremely racist and difficult circumstances. Furthermore in a sense, Clarabelle is no different than the "S O Bs in ties and coats" that mislead the Filipino workers with promises of good jobs and good wages (1). She also represents the fantasy of Filipino workers during that time achieving the American dream. Nick refers to her as a "phantasm" and "a chimera" (23). Despite the literally insurmountable obstacles of anti-miscegenation and discrimination laws, Magno Rubio is tragically optimistic in chasing that dream.

This play captures a significant time in American history and Filipino American history. In 1924, Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act which banned the immigration of Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and other South Asians to the United States. Pilipinos, however, were exempt from this law because of U.S. colonization in the Philippines, which allowed them to emigrate. As a result, Pilipino immigration soared, and Pilipinos became the primary source of cheap labor in many sectors, especially agriculture (Sterngass 43). Often single males, Pilipino laborers were regulated to "stoop labor" which refers to exhausting hours of bending down to harvest crops. During the Depression era, even Filipino college students, like the character Nick in the play, were forced into agricultural labor (Espiritu 4).

Sterngass, Jon. Filipino Americans. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing, 2006.

Back to Top

I was both excited and surprised by the ample stage instructions and descriptors that Momoko Iko wrote into the play. Though the play drew similarities to her own family, it was not exactly her experience. However, the detail that Iko provided in the script ignited my imagination and it seemed like the events and characters were from actual memories. Roberta Uno's introduction of Iko and the play accurately described the sense that I received from the play. She writes, "...she challenges the myth of Japanese American complacency in the face of the evacuation order, dramatizing the range of responses to that edict" (108). From what I have learned about Japanese internment history in the past, the discourse seems to portray Japanese in the U.S. during that time as the complacent "silent minority," devoid of individual thought. During this time the Japanese in the U.S. were subjected to extreme prejudice and were left powerless. It is also true that culturally the Japanese are collective and contextual, as opposed to individualistic, but Iko breaks the notion that the Japanese were a homogenous mass of thought and action. From Hiroshi and Tadao's angry idealism to Kimiko's pragmatism, Iko displays a wide and colorful spectrum of responses towards the war and the evacuation order, allowing us truly view and value Japanese Americans of that time as separate individuals and with human dignity. If I could portray a character from this play, I would portray Masu. Though I could never actually imagine myself "being" Masu and understanding the depth of his internal struggle, I find his character the most fascinating. Like Uno describes, Masu was a man with a "rebellious nature and poetic soul," whose "frustration is that of a man embodying a collision of cultures" (107). The culture of pride and shame is so ingrained in his nature that it is almost painful to read Masu's scenes. He is ashamed of not being able to provide for his family and relate to his son, and his pridefulness further restricts him. Intertwined with the shocking events of the war and internment, Masu makes for a complex and tragic character. To prepare for this role, I would especially have to "play the action" rather than "play the words" because I don't personally connect with Masu in any way. I would try to capture the emotion behind Masu's words rather than focus on memorizing his words. Through reading stories and memoirs, I also would do some more research on the "tension between individualism and dynamics of the group" that Uno describes in attempt to capture all of Masu's words left unsaid through emotion. Back to Top

Back to Top

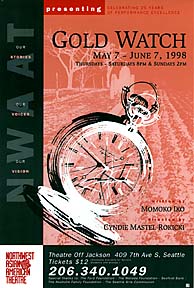

The Gold Watch by Momoko Iko

Set in the Pacific Northwest during the fall of 1941 and late spring of 1942, The Gold Watch centers on the lives of the Murakami family, a Japanese farming family. The central conflict surrounds the family, particularly Masu and Tadao's responses to World War II and the discrimination and internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans from the war's anti-Japanese hysteria. The play reveals dramatic cross-generational differences that caused tension within Japanese families during that time. |

| Playbill of the Gold Watch at Northwest Asian American Theatre (Seattle) in 1998. Source: Google Images |

12-1-A by Wakako Yamauchi

Wakako Yamauchi's 12-1-A exposes the Japanese and Japanese American incarceration experience in U.S. internment camps during World War II through the story of the Tanaka family in a Poston, Arizona camp. Mrs. Tanaka, Mitch, and Koko, are both appalled and rattled to their cores by the injustice carried out on them when they are sent to an internment camp. Quickly, they make friends with other Issei (immigrants from Japan) and Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans born in the U.S.) in the camp. Through their struggle to make sense of their plight, Yamauchi challenges the inhumanness of the incarceration with each character's humanness.

The play did not have any particularly scenes that you would describe as "exciting" with the same dusty backdrops for nearly every scene. Obviously, this is to be expected because it is a play centered on experiences in a internment camp in the middle of a desert. However I found this interesting because the Poston, Arizona camp was an actual camp in history. It is ironic because the dusty and desolate setting of this Poston camp symbolizes the turmoil and isolation felt by the incarcerated Japanese Americans.

During World War II, Yamauchi and her family were incarcerated at a camp in Poston, Arizona. Though not explicitly, this play is reflecting Yamauchi's own experiences. The significance of this for both the development of the Asian American community and American history is best expressed in the scene where Ken is called an inu, or "dog," and attacked for possibly being an informer on others in the camp. Mrs. Ichioka, Ken's mother is both afraid and impassioned about this. Ken explains to her that he's recording observations and reactions of every thing that is happening in the camp. He tries to stress the importance of writing these reports, "After they happen, Mom. It's going to be important one day" (80). Similarly, this play is an important record, or report of what happened. The characters in 12-1-A may not be actual people in real life, but they symbolize the unique spirits and voices of an entire disenfranchised people in American history. Yamauchi also deconstructs the historical narrative by gendering the discourse on these events especially through the characters of Mrs. Tanaka, Koko, and Yo. For Japanese and Japanese American women, the incarceration did not just mean a time when they were oppressed as a race, but it was a time when they felt powerless as women. Yo expresses this when she describes the barracks for the single, Japanese women, "You should see us at night--all line up in a row on these narrow beds--like whores in a whorehouse...” (50).

Below is a video I found of some people acting out Act 1, Scene 3 in the play:

Acting Journal

I learned --at least I gleaned a sense of-- what an autodrama is today. Acting is being; it is a complete surrender of your mind and body. As Professor Tanglao-Aguas described, as actors we are both "vassals and vessels." I found that when I was reading the words I wrote about my sister, there were so many things left unsaid. I did not feel like I properly expressed what I wanted to convey. My older sister is someone that has always been a defining role model in my life, who helped shape who I was and am. Although I was reliving memories of my childhood with my sister -- driving trips to Shenandoah Valley with our dad on Wednesday mornings, helping each other eat our disgusting vegetables -- I still felt like I was "acting," not "being" the role of myself. I felt separated from the experience that I was describing. I think that was the outcome of two layers: feeling unconfident in myself and not wanting to reveal too much. First, I felt that my story (that is, my life experience) was not good enough to tell especially since I felt that I don't have an extraordinary talent or exciting event that shaped who I am. But everyone's stories are important, right? In fact that's what I wrote on my college admissions essay. I love hearing people's stories and exploring what and how they define themselves, and how history and circumstances around them have influenced that. That's what is beautiful about stories and in a sense "acting"; you get glimpse of who a person, character, or what the larger idea they are embodying is, and you get to really "see" them. So secondly, I realize now that I was playing it safe. As much as I wanted to believe that I was, I was not being vulnerable. Rather I was presumably restricting my own agency through that. My motivation, action, and objective fueling my autodrama piece preparation and performance was the hope that I could just be done and not do anything extremely embarrassing. If I could re-do my autodrama, I think I would choose to do something completely different. I would try to overcome my fear of acting and actually act out a defining moment that has happened in my life instead of just reading about it.

My scene partners are Felicia and Tommy. We decided to take an unconventional approach by performing parts of scenes from Paper Angels. Felicia is Ku-Ling, Tommy is the Inspector, and I am Chinmoo and Mei-Lai. Through our performance we wanted to give a glimpse of these characters and the intertwining yet clashing ideologies about identity and experiences at the Angel Island Detention Center. The most difficult component in portraying my two characters was to grasp the intention behind the words, especially with Chinmoo. In the scene, she tells the other women that the three months she has spent at Angel Island count as nothing compared to the forty years that she waited for her husband. After six months of blissful marriage, her husband "had itchy feet" and left her to try his luck at Gum San. To prepare, I tried to use dramatic analysis on her lines in the script but I found it difficult to understand her "objective(s)" like we discussed in class. Is Chinmoo just simply trying to convey her story to the other women? Is her objective to show regret? If so, how does that change the way I portray her? I also tried to envision her underlying emotion and thinking process. It was hard to understand, so I imagined this part of her life in my head -- what she said, what he said, what they did-- as if the scenes that she describes happened to me. Afterwards, it was much easier to feel the complex emotions I am sure Chinmoo would express. I felt nostalgia, bitterness, disappointment, sadness, and acceptance. In my opinion it was easier to portray Mei-Lai because I felt like I understood her character more. It seemed like her objective in the scene was to scold or criticize Ku-Ling. She is younger than Chinmoo, so I decided to remove my glasses and let down my hair to distinguish the differences and the transition between the two characters. The playwright describes Mei-Lai as a young wife who "possesses all the virtues of an ideal Chinese woman" but also has a "profound sense of loss and insecurity underneath her outward appearance." My portrayal of her turned out to be completely different from what I initially imagine her to be. I realized that she does not have to be a completely meek and gentle character, her interaction with Ku-Ling attests to that. Her words, "There's a name back home for girls with unbound feet who wander on their own,"are deviously insulting, so I decided to portray her with a more condescending persona. Regardless, I am excited to see everyone's performances in class. Back to Top

Acting Journal

I was impressed by the scene performances last class. It was everyone's second time performing their scenes. For most of the performances, I could see the improvement in terms of comfortableness on the stage. I think that having performed the scenes once already, everyone seemed comfortable enough with their lines and roles that they felt more freedom with what they could do onstage. That seemed to be the case for my group as well. Though I felt more comfortable after having performed it once, I felt more nervous at the same time because I wanted to improve upon my previous performance. Professor Tanglao-Aguas explained last class that it was important to let the words and actions "breathe" before calling "scene" at the end. Another advice that he gave was for everyone to "surrender" more. I think surrendering in different aspects of the class has been a huge difficulty for me throughout this first half of the semester. There were times that I wanted to volunteer to do a scene or be part of an in-class exercise in front of the class, but I was afraid so I chose not to. So, I was determined to "surrender" more for this performance because I did not want to regret it. Before we started, Professor Tanglao-Aguas told me and Felicia to "let it rip" between Mei-Lai and Ku-Ling's bickering. I didn't know exactly what that meant---are we allowed to add more to the dialogue in the script? If not, what more should I do to enhance it without changing it? I ultimately decided not to try and change anything mostly because I didn't have any ideas of what "Mei-Lai" would do. I knew previously that Mei-Lai and Ku-Ling were insulting each other, but perhaps from the cultural and generational gap I didn't really consider what they were actually insinuating. So when "Ku-Ling" made the comments about "my" feet, I replaced the words in my head with (possible) present-day equivalents -- slut, whore, tramp, etc. What changed was that I moved much closer to Felicia's face and I interrupted in the middle of her sentence with a loud "EXCUSE ME?" It was psychosomatic because I felt like I was simply "reacting" to the insult. Though it wasn't groundbreaking, I count it as a victory because I was allowing myself to "be" in that moment. Overall I was satisfied with my group's performance because we did our best to "surrender" and take chances on the stage. It certainly wasn't perfect, but I think that we made a better and more creative use of space throughout the scene, instead of only standing in one place. Back to Top

Acting Journal

It was nerve-wracking hearing Professor Tanglao-Aguas tell Andy and Nikki to repeat their scene in Gold Watch over and over. First, we established that Masu's objective was simply that he wanted to drink and Kimiko's objective was that she wanted Masu to stop drinking. Second, Professor Tanglao-Aguas told them to begin the scene instead with Kimiko knocking on the door while Masu is inside trying to open his bottle of sake. Andy and Nikki must have repeated this scene between Masu and Kimiko more than five times. What was Professor Tanglao-Aguas looking for in that scene? Each time that they repeated the scene, Nikki or "Kimiko" knocked for a longer period of time. The tension was palpable! How was Andy or "Masu" going to react. After a few times I started to get more invested, and even annoyed, from the persisting knocking. Just as Morris suggested in our discussion afterwards, the most real moment was when Andy (Masu) abruptly yelled at Nikki (Kimiko) in the scene that he couldn't stand the knocking in a burst of frustration. I think everyone in the class yelled the same thing in their heads. Professor Tanglao-Aguas was trying to teach us through this experience that acting is reacting. Though the first rule of acting is to "only do what you are supposed to do," Meisner's second rule is to "only do something else when something else happens that makes you do something else." When Andy and Nikki started to really pursue the objective of their character, their reactions to changes in the script seemed instantaneous and more authentic. Applying these rules to my own work with my group members, I found that trying to grasp the objectives of each of our characters. I thought that it was difficult because for most of our scene, we were performing snippets that partially or did not happen during the same scene within the original script. However, I found it much easier for us to portray our characters when we did not pay as much attention to our lines, but listened and reacted to each other in the scene. It sounds rudimentary, but it was one of the most important things that I learned working with my group partners. When we were actually listening to one another, the words flowed more easily and "reacting" became much easier. We were able to give each other better feedback and constructive criticism. Furthermore, when we forgot our lines, it was more helpful if we were paying attention to the actual interaction within the scene, and we could continue without stopping by "playing the action." Back to Top

The term “actor" I think belies what "acting" actually expects of you. In class we discussed "acting" as "being" the character. In essence, I would argue that you are giving pieces of yourself to each of your characters. Even if you have a vastly different experience or life than the characters you are portraying, there is always something you can find in common with them for the simple fact of being human. Human emotions, feelings, actions all have elements and nuances to them that are simply either universally perceived, felt or understood. For example, like I discussed in my play report on the Gold Watch, for the character of Masu I am the complete opposite. It is difficult to relate to Masu because he is a man and I am a woman. He is a father with many life experiences that have hardened his heart, while I am a college student trying to get through school, but yet has so many hopes and expectations for the future. So how am I to play a character that is so different from myself? How could I possibly do this character's life and experience justice? Like we learned in class, in dramatic analysis of plays-- behind every line in a script-- you will find causality, where every line is geared toward a purpose or objective. When you focus on the objective, you will find the emotion of the character. So, when I am portraying a character, I am not changing myself to become this character, rather I am becoming this character in this moment by expressing the action or objective of the character. Removing the obvious differences, Masu and I --and perhaps between humans in general--share the quality of humanness. Through that I am able to better portray facets of Masu than if I simply try to "act" the lines. What human being has never allowed their pride to get in the way of a relationship that they care about or felt shame for not measuring up to an expectation? Now, most likely I would not portray Masu because I obviously do not bear comparable physical qualities, and I would not want to mess with the playwright’s intentions. My point is that being an "actor" or "actress" is identifying the most basic objective (which is often the most "human") of your character, realizing the part of you that connects with it, and translating your experience of that action to live in that emotion that your character is feeling. Once you make that connection, you are also in a sense making yourself vulnerable---and it is something that you cannot take back. It is still unclear to me if the portrayal of a character "adds" something to the actor, but I believe it certainly expands the actor's capacity to understand, relate with others. Back to Top

Acting Journal

Midterm Question 1

Wakako Yamauchi's 12-1-A is a powerful work that illuminates an important and terrible offense in U.S. history. During World War II, the U.S. government authorized and carried out the forced removal and imprisonment of thousands of individuals with Japanese heritage. I found it the most significant in our study of the Asian American community not because the Japanese American experience is more telling, but because it symbolizes a need for awareness, social activism, and solidarity within the Asian American community. As we know, the Japanese American incarceration was not the first nor last of racial discrimination and prejudice against Asian Americans.During a war where the United States was fighting for its freedoms and ideals, it performed one of the most extreme encroachments on the civil liberties of American citizens. Under President Franklin Roosevelt's executive order, Japanese Americans were detained without trial and due process not because of any wrongdoing, but simply on the basis of race --they looked like the enemy.

|

A sign at the Manzar Relocation Center.

Credit: Ansel Adams; Library of Congress

|

A Naval intelligence report in 1941 stated,

[the] Japanese problem . . . is no more serious than the problems of the German, Italian, and Communistic portions of the United States population, and, finally that it should be handled on the basis of the individual, regardless of citizenship, and not on a racial basis (Densho).Despite this, FBI carried out searches of Japanese American homes for "prohibited" items such as radios, cameras, and heirloom swords. In January 1942, thirty-two Japanese immigrants and citizens were detained under harsh conditions at an abandoned campsite in Clovis, New Mexico. They spent a year there and were eventually moved to concentration camps after the executive order was issued. The next month in February, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to remove civilians from any area and detain them. Though order did not specify any particular group, only Japanese Americans were imprisoned as a consequence of the order. Executive Order 9102, established the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to manage the "assembly centers" and "relocation centers."

America's wartime alliances polarized public opinion and pitted "good" Asians—e.g. Chinese, Korean, and Filipino Americans—against the "bad" Japanese enemy. For the most part, non-Japanese groups accepted the wartime racialization of the Japanese and, in some cases, actively encouraged it (Hong).

As an Asian American, this event to me represents not only an important part of history, but an important event in the development of the Asian American community.

References Densho. Sites of Shame. <http://www.densho.org/sitesofshame/index.html> Hong, Jane. "Asian American response to incarceration." Densho Encyclopedia. 19 Mar 2013, 17:22 PDT. 28 Feb 2014, 20:15 <http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Asian%20American%20response%20to%20incarceration/>. Back to Top

Midterm Question 2

At the beginning of the semester, I would have said that I did not really see agency in acting, especially when you are limited by the script, the director, and other actors. Now, through our acting and study of Asian American plays and history, I can see that acting is a form and expression of agency in multiple ways. Agency is defined as "the power of individuals to act independently of the determining constraints of social structure." By actively engaging in these plays, I am creating agency because as an actor I am challenging the structures surrounding identity, specifically Asian American identity, in performing these plays. Personally, this is where I am empowered because I can express how I see Asian American identity through non-racist, dynamic Asian American characters. There is also the agency of action. We discussed this at length in our class exercises and discussions. As an actor, your character will always have an action, and behind that action an objective and a motivation. That is where an actor's agency flourishes because every line, word, and action has a purpose. How the actor achieves the objective is up to them. Just like in Boleslavsky's Second Lesson, where just the image of cucumbers conjures up an emotional connection, memory of emotion, it is up to me as the actor to create that context for my character. That context can come from my own experiences and memories. I feel that just studying these Asian American plays gave me the opportunity to critically think and give context to my own experiences as an Asian American. From racial slurs and ignorance from my peers growing up, I could relate to the feelings of displacement and Otherness that many of the characters felt. With our study of these plays, we as a class have created a space for this kind of open dialogue. Right now, I feel as though I have not completely surrendered to the process. My plans are to articulate the things that I am learning to my peers more often, and to take more chances in class rather than keep mostly to myself. Back to Top

--end of document-- Back to Top

Special Collections Wiki

--start of document--

Priscilla Lin

New Special Collections Wiki for South Asian Student Association

The South Asian Student Association (SASA) is an undergraduate student organization at the College of William and Mary dedicated to promoting cultural unity, identity, and awareness. It is one of the College's multicultural organizations, consisting of members with heritage from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and other South Asian countries, and members with an interest in learning about South Asian culture.

Mission

Mission Statement

“The purpose of the [South Asian Student Association] is to promote awareness of the South Asian culture and of all members of the College of William and Mary and its community; to provide social and educational activities for all interested individuals; to promote identity and unity among the South Asian Students of the College of William and Mary.” [1]

Objectives

- Educate the William and Mary community about South Asian heritage through educational, charitable, and social events

- Encourage students to learn, experience and continue South Asian culture

- Present forums to address critical issues that pertain to South Asian students living in the United States

- Provide a nurturing and positive atmosphere for members of the College community interested in learning more about South Asian culture

History

The Indian Cultural Association

The South Asian Student Association was previously known as the Indian Cultural Association (ICA). ICA was founded by students Abita Sachdev ('93) and Raxa Desai ('92) in 1991. The foundation years for ICA were 1992-1993. ICA was renamed SASA in 2002 to better represent its members.

Executive Board and Membership

- 1991 – 1992

32 members

Co-Presidents: Abita Sachdev, Raxa Desai

Treasurer: Soumya Viswanathan

Secretary: Saroj Sheshadri

Publicity Chair: Brian Caton

Social Committee: Shefali Sharma, Nadini Koka

- 1992 – 1993

42 members

President: Abita Sachdev

Vice President: Soumya Viswanathan

Treasurer: Fiasal Riaz

Secretary: Shawn Sharma

Asian Student Union Representative: Nidhi Singh

Publicity Chair: Saroj Sheshadri

Social Chair: Jaya Chimnani

- 1993 – 199428 members

- 1994 – 199557 members

- 1995 – 199661 membersPresident: Dharmesh Vashee

Treasurer: Rafay Alam

Secretary: Harshad Daswani

Publicity: Sarah Watson

Asian Student Union Representatives: Kaustuv Chakrabarti, Crisha Chachra

Social Chair: Nisha Rao

- 1996 – 199783 members

- 1997 – 199858 membersPresident: Maria Iqbal

Vice President: Arti Shah

Secretary: Taha Haidermota

Treasurer: Pamela Kanal

Publicity: Gazala Ashraf, Rabia Tajuddin

Historian: Sarah Watson

- 1998 – 1999President: Kulwant Singh

- 2001 – 2002

President: Davina Vaswani

Officers: Hamza Azim, Joshbeen Grewal, Martha-Alice Kiger, Nirav Mehta, Kishor Nagula, Nisha Patel, Rehana Raza, Amola Shertukde

- 2002 – 2003

President: Harsha Nagaraja

VP: Rehana Raza

Secretary: Nisha Patel

Treasurer: Palak Oza

Publicity: Dnyanesh Kamat

Historians: Nirav Mehta, Ahsan Iqbal

Webmaster: Devang Patel

- 2003 – 2004

President: Davina Vaswani

VP: Harsha Nagaraja

Secretary: Amol Patel

Treasurer: Palak Oza

Publicity Chairs: Amola Shertukde, Vivek Ramakrishnan

Webmaster: Devang Patel

Social Chairs: Neha Patodia, Richa Gandhi

Historian: Shivani Desai

Freshman Rep: Nadina Perera

Webmaster: Devang Patel

- 2004 – 2005

President: Etaf Khan

VP: Shivani Desai

Treasurer: Richa Gandhi

Secretary: Amol Patel

Social Chair: Meera Doraiswamy

Public Relations: Akshay Jakatdat, Krishnan Vasudevan

- 2012 – 2013

President: Prateek Reddy '13 Vice President: Pratik Thakral '13 Secretary: Nuha Naqvi '15 Treasurer: Sitara Sundar '15 Social Chair: Konark Bhasin '14 Public Relations Co-Chair: Hareesh Nagaraj '15 Public Relations Co-Chair: Shyam Menon '14Historian: Sonia Talegaonkar '15Outreach Chair: Soumya Tippireddy '15Freshman Representative: Sudeep Kalkunte '16Expressions Co-Chair: Deepak Chitnis '13Expressions Co-Chair: Richa Patel '15NKD Co-Chair: Harmeet Kamboj '16NKD Co-Chair: Bindu Sagiraju '15

Annual Events

Expressions

Expressions is SASA's largest annual performance and entertainment night in the fall semester. ICA began hosting the Expressions Night to celebrate Indian culture with Indian food and entertainment. SASA expanded Expressions Night to include celebration of cultures from South Asia in 2002.

- 1994 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Oct. 22, 7 p.m. in Tidewater

- 1996 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Nov. 9, 7 p.m. in Chesapeake

- 1997 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Nov. 15, 7 p.m. in Trinkle Hall

- 1998 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Nov. 7 in Chesapeake

- 1999 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Nov. 12 in Chesapeake

- 2001 – “Expressions of India: An Evening of Indian Food and Entertainment” on Nov. 9

- 2002 – “Expressions: A Celebration of Cultures from South Asia”

- 2007 – “Expressions: A Balancing Act”

- 2011 – “Expressions: The Princess and the Frog Goa Edition” on Nov. 11 in Commonwealth

Nach Ke Dikha (NKD)

Nach Ke Dikha is an annual intercollegiate Bhangra & Fusion Dance Competition hosted by SASA and the College (source: http://wmnkd.com/). SASA began hosting NKD in 2011.

This week we are deciding on topics for our thematic projects and creative projects. I had an easier time thinking about my thematic topic because a "creative" project seems quite daunting, especially since sometimes I get too focused on generating an "one of a kind" idea for the sake of just being "creative." For my thematic topic I decided that there are two potential topics for me to explore: Asian Americans and the model minority myth or the role of religion in Asian American communities. Responding to problematic perceptions and stereotypes of Asian Americans may be a salient topic that I could find interesting current events to relate to. For example in 2012, the Pew Research Center released a report called The Rise of Asian Americans, perpetuating the model minority myth. Here is an article discussing the response of the Asian American community: http://colorlines.com/archives/2012/06/pew_asian_american_study.html. Most people do not know --because of media stereotypes-- that amongst some Southeast Asian communities in the US, high school drop out rates are the highest in the nation. I'm certainly not an expert, so this would be an informative topic to do research on. Another possible topic would be to analyze the role of religion in Asian American communities. I do not know much about religion and Asian Americans in scholarly literature, but from my initial research in Swem references, this book may be a good place to start: Asian American evangelical churches : race, ethnicity, and assimilation in the second generation. This book features two case study examples: one of a Chinese American church and one of a Korean American church, and analyzes how they are each situated in American Christianity.

Later in this week - I have decided to narrow down my thematic topic to Korean Americans and Christianity. We have not covered or learned about the Korean American community in class, so I would like to do research on this community. I think it would be a worthy topic to discuss considering the growing trend of Korean and Korean American ethnic mega churches in the United States. I grew up in Northern Virginia, and all of my Korean American friends attended Korean churches. Religious content seemed to make up a significant part of their culture and their lives.

For my creative project, I have decided to focus on Asian Americans at William and Mary. I will conduct a mix between an oral history and photoblog project to work with the Asian American Student Initiative, and raise awareness about Asian American issues on campus. I am definitely inspired by Humans of New York , which is all about people's stories and identity formation. I think this would also be a great opportunity to strengthen coalition-building with the Asian American community and also across William and Mary communities for advocacy. I will just need to find a photographer!

Back to Top

Acting Journal

For my Researching Asian Americans at William and Mary (RAAWM) project, I decided to focus on the Indian American community at the College. Though scope of this course did not include the study of Indian Americans and other South Asian American communities, they are part of the rich, intricate fabric of the Asian American community whose stories must also be told. When I began my research at Special Collections, I decided immediately to try and find some demographical information to try to understand the previous racial makeup of William and Mary. I wanted to find information on when and how many did Indian Americans start to attend William and Mary. However, the Special Collections staff did not seem to be optimistic when I told them I was researching Indian Americans at William and Mary, because of the lack of data available. The Special Collections staff recommended that I explore the affirmative action reports, which included information on minority students at William and Mary. Perusing through piles of affirmative action reports from 1977 to 1989, I did not find much notable information particularly because most reports prescribed to a specific format that didn't specify separate racial groups other than white or black. Asians were attributed to one group, without any other subcategories, and the data only showed the percent change in number of new students of that report year. There was also another category for "other racial groups," but there were not specificities on what groups were included in that category. In the section of Profile of Minority Students, there was consistent and repeated use of the word "oriental" to describe Asians, different aspects of available programs and activities, and specific goals of the College. I found that problematic because traditionally the term "oriental" was used to refer to the "east," particularly cultures of East Asia, which typically suggests to not mean India and other South Asian or Southeast Asian countries. The term "oriental" in Western culture has been constructed to evoke perceptions or images of people of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Southeast Asian identities. Consequently I concluded that it is possible that in the reports, the text may not have considered people of Indian descent as "Asian" in its discussion on "oriental people." This is when I discovered how meticulous and challenging archival research can be. With the information gap, I discovered that I certainly couldn't make any clear assumptions on the first Indian Americans at William and Mary. I decided that I should focus in on researching a student organization for Indian Americans at William and Mary. Already existing was a link to the Indian Cultural Association (ICA) on the wiki, which redirected to the South Asian Student Association (SASA) wiki page. Evidently, ICA was the predecessor to SASA, which was renamed from ICA to SASA to reflect the broader representation within the group. The page for SASA right now, like the other Asian cultural organizations' wiki pages, is scant and does not have much information. I think now I will renovate and expand the SASA page to include more than the description of the organization. Back to TopActing Journal

Unlike last semester, we are attempting to truly put to practice agency and student-centered learning pedagogy this semester. I've learned that I work well in this type of setting because I enjoy the freedom of choosing what I want to explore and my methods in doing so. However, I learned that there are also caveats to this type of learning for me. Our catchphrase for the semester has turned into "Up to you" but I realized that not everything is "up to me" because there are still specific class objectives and requirements that this course must fulfill. It was also challenging for me because I work better when I have specific deadlines for myself. But I did not take that route this semester, which in hindsight would have helped me a lot. I had to learn how to exercise my agency (and feel like I was doing it) in the context of the bounds already in place. Though everything has been a lot of work, I would not take back or change anything that we've done this semester.

Another way I have been thinking about agency in the classroom is with our preparation for our class performance night. After a few classes, despite Professor Tanglao-Aguas' urging and Rachel's initiative, I was surprised at the rest of the class' and my own apathy to the preparation process holistically. I knew for a fact that everyone was spending a great deal of time and effort on their creative projects. Didn't we all want to see the endgame or culmination of our hard work? Or are we all doing this just for the grade? I don't know about everyone else, but from what I have seen in the caliber and dedication of the class, I didn't think so. I realized that for me, when you receive agency or are placed in a space where you can exercise agency, with that comes great power and necessity. It sounds cheesy, but isn't it true? The high value that we put on "agency" in our society today has no meaning if you don't attempt to harness it and use it in your way. I guess that I could also say that it was in my agency to decide to do nothing to help with the preparation. However I realized that this was an opportunity to do create something creative and also to bring people together -- I love both of those things. So I decided to go ahead and do what I could. I decided to name the event myself and make a flyer for it. I also created the Facebook event and had the opportunity to talk to many of my friends about what I was doing in this class. I'm glad that I had the opportunity to do that because otherwise I would have missed out on a chance to do something simple that was not only fun but rewarding for me. Below is the final flyer for APAHM Night.

Thematic Paper

Priscilla Lin

5/5/14

Second Generation Korean Americans and Christianity

In April 2014, out of the 25 Asian Americans at the College of William and Mary that I interviewed as part of an Asian American identity study and project, three students identified as Korean American. One out of the three also identified himself as “Christian.” Reflecting on his experience as a Christian and Korean American, he said,

I grew up in a culture where everything you do that is related to Korean American culture - the food that we eat, the types of relationships you form, the social hierarchies that you learn - all comes through developing an identity through the Korean American church.

This intersectionality of religion and ethnicity for Koreans in the United States is not uncommon due to the importance of religious institutions in Korean American life. In fact, most of the 1.7 million Koreans in the United States identify themselves as Christian. According to Pew Research (2012) and R. Kim (2006), more than 70 percent of Koreans in the United States describe themselves as Christians and attend Sunday services at a Korean ethnic church regularly. The interaction of religion and ethnicity in second generation Korean Americans (SGKA), meaning children of first generation Korean immigrants, is a broadening study area particularly because of evangelical phenomenons on university campuses, the increase of second generation churches, and issues of multiracial evolvement in churches (R. Kim, 2006; S. Kim, 2010). In this paper I will discuss relevant findings from my study of Asian Americans at the College of William and Mary and draw together examples from case study findings of scholars on Korean American Christian identity, to examine how second generation Korean American (SGKA) Christians negotiate their identities.

Tensions of a Marginalized Identity

Most Korean American Christians attend Korean ethnic churches rather than multi-racial or white churches. Though Korean ethnic churches are certainly not all synonymous to one another, most Christian Koreans in the United States describe themselves as Protestant-- more than 60 percent (Pew 2012). Consequently, a similar SGKA narrative of ethnic and religious experience can be drawn across denominations. Why do most Korean Americans gravitate towards only ethnic Korean churches? Chong’s (1998) study of two Korean American ethnic churches in the Chicago area shows that discrimination and prejudice based on race or color can catalyze stronger solidarity and community along ethnic lines and involvement in an ethnic church. Most of the respondents attributed their perceptions to their experiences in college and as young adults, “I think American society is most outrageous and unjust. It’s still so racist...since college...Once I started to notice, I saw it everywhere. US is not a melting pot. We’ve got a lot of problems” (Chong, 1998, p. 268). Chong (1998) further posits that these perceptions become identity crises for Korean Americans, especially second generation, driving them to be more comfortable in worshipping and practicing their faith in ethnic Korean churches rather than the mainstream. This suggests that their perceptions of their marginalized ethnic identity is also critical to shaping the existence or maintenance of their Christian faith.

Sense of Togetherness: the Church and an Empowered Group Identity

The ethnic Korean Christian church plays a significant role in generating a sense of ethnic unity and values. As enclaves of where traditional Korean cultural structure is in place, as well as expression and dialogue of contemporary Korean pop culture, all intermixed with expressions of Christian faith, these churches seem to provide SGKA Christians an alternative route to assimilation into Anglo-conformity and Christianity. According to a respondent in Chong’s (1998) study, it created a sense of empowered group identity: “In church, I found God. Although I have some problems with Korean churches, I get a lot out of it. In church, I felt my ethnicity affirmed. There, it was OK to be Korean” (p. 268). The church also creates and maintains social networks and fellowship. When asked why they attend a Korean ethnic church, a respondent remarked, “It’s trying to find a group that’s comfortable. Lots of kids from white areas come to church to relate to Korean friends. There is a sense of comfort in being with other Koreans or Asians because there’s an understanding in terms of background. For example, all Asian parents are strict. Korean Americans have an unspoken understanding that we’ve all been there, like experiences of prejudice” (Chong, 1998, p. 267). Furthermore, members generate social capital by becoming each other’s support network.

Primordial ethnicity theorists argue that the continuity of historical and cultural ethnic bonds impact communities intergenerationally within strong, rigid boundaries. In other words, the concept of ethnicity for communities does not change because of these lasting ethnic bonds. For example, some researchers find that Koreans, often first generation immigrants, perceive churches as the primary vehicles of cultural transmission from the first generation to second generation (Chong, 1998). Ethnic and cultural values on morality, work and behavior are all transmitted through the religious space. Encapsulating cultural aspects and nuances into the culture of the church, scholars argue that the churches have the “capacity to strengthen and reinforce ethnic identity” for both the first generation and second generation (Bramadat, 2012, p. 4). Consequently, the church is not only a religious space for Korean Americans, but an important cultural and social space. The church in effect is the space in which Korean American Christians can negotiate their identity.

Tensions of Intergenerational Difference in the Church

However, like other ethnic communities, second generation Korean Americans differ from their immigrant parents in negotiating their ethnic and cultural identities. In contrast to the first generation, second generation Korean Americans do not have the same obstacles in linguistic proficiency and cultural barriers. Moreover, this is emphasized in terms of identity politics, where there is often the identification with and the sense of a hyphenated identity, in which second generation Korean Americans do not feel fully Korean nor fully American. In my research study, to the questions of “Who are you? How do you identify yourself?”, a Korean American interviewee responded with “Who am I -- that’s something I’ve tried to grasp for a very long time in my life. Am I Korean or am I American? Or am I both?” Much of this conception of an ambiguous and hyphenated identity draws to not just behavioral discrimination, but also systematic attitudinal discrimination and prejudices based on race, color, and ethnicity. This is a phenomenon also extends to other Asian Americans. Other respondents in my conducted interviews also commented that it was difficult for them to understand and perceive their ethnic identity.

As part of this phenomenon, SGKA Christians struggle to resolve their ethnic identity and what that means for their religious identity, and vice versa. According to R. Kim (2006), “SGKAs characterize the first generation’s religious participation as hierarchical, patriarchal, and static, and they describe their own as democratic, egalitarian, and dynamic” (p. 43). This has created intergenerational and intercultural tensions within the ethnic church.

Creating New Hybrid Identities

Differences in practical needs, religious participation and cultural and social ideology between the first generation and second generation have led to ethnic churches dividing their congregation into two separate ministries, one Korean-speaking ministry primarily catered to first generation Korean immigrants, and one English-speaking ministry primarily catered to second generation Korean Americans. R. Kim (2006) reports that the English ministries in ethnic churches are “led by 1.5 or SGKA pastors and staff or even by some non-Korean Evangelicals who are trained in American seminaries,” while the Korean ministries are led by pastors trained in Korea (p. 42). In effect, the various intracultural and intergenerational tensions have created spaces for SGKA Christians to worship and practice their religious and ethnic identity in their own way.

Now there is also a movement with second generation congregations leaving the first generation ethnic church to start their own church (R. Kim, 2006; S. Kim, 2010). In her study of 22 independent second generation Korean American churches, S. Kim (2010) notes that the SGKA of the study, unlike immigrant parents, fulfill all the paradigms that suggest assimilation in the mainstream society to the extent that they would “‘fit in’ and feel ‘at home’ in mainstream churches” (p. 6). However, they still choose to organize as separate ethnic churches of their own.

Conclusions

For second generation Korean American Christians, Christianity and SGKA ethnic identity are reflexive. They are both dynamic elements of identity that inform and construct one another. The effects of each are not unilateral. How second-generation Korean Americans understand their faith is connected to how they understand their ethnic identity. At the same time, their faith constructs their ethnic identity.

The ethnic cultural and social aspects of the first generation immigrant church created a resistance from the second generation church. Sharon Kim calls the new kind of faith that they construct for themselves--taking aspects of “Americanized” Christianity and Korean culture and faith---a “hybrid spirituality” (pg. 8). More than that, SGKAs have constructed a sort of defensive ethnicity in response to the generational, cultural, and social differences stemming from a specific ethnic identity created by the first generation. They have created an ethnic hybrid spirituality and ethnicity by exercising an agency to choose what values, ideologies, and practices that they want in their churches.

References

Bramadat, J. (2012). The role of religion: Inter-temporal ethnic and cultural identity formation among first and second generation immigrants. Journal of Religion and Culture,

Chong, K. H. (1998). What it means to be Christian: The role of religion in the construction of ethnic identity and boundary among second-generation Korean Americans. Sociology of Religion, 59(3), 259-286.

Kim, R. Y. (2006). God's new whiz kids? : Korean American evangelicals on campus. New York: New York University Press.

Kim, S. (2010). A faith of our own : Second-generation spirituality in Korean American churches. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Pew Research Center. (2012, July 19). Asian Americans: a mosaic of faiths. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/files/2012/07/Asian-Americans-religion-full-report.pdf

Back to Top

Clybourne Park Performance Report

I was an usher for the Saturday night performance of Clybourne Park. Honestly, I did not know what to expect. I had never read Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun, so all that I knew about the play was that it was about black/white gentrification in the late 1950s and the present day. Thinking along the lines of the previous plays that we read in class, I thought that with a topic like race relations, it might be a serious play based off of a true story. I was pleasantly surprised.

Bruce Norris' Clybourne Park uses comedy and satire to explore the issue of race, color, and difference. In Act 1, Russ and Bev prepare to move out of their home in Clybourne Park after the loss of their son who committed suicide. Their neighbor tries to convince them not to leave because the house was sold to a black family, and he fears that the property values of the homes in Clybourne Park would decrease from a black family moving in. In Act II, the same actors play different roles. It is in 2009, and the roles are reversed. Clybourne Park over the last 50 years has become a historically black neighborhood, and white gentrification is occurring with a white family moving into the house. The play ends with the construction worker discovering Bev and Russ' son's final letter to his parents, saying that he believes things are going to change for the better.

Bev and Russ' son's last words are ironic, and seem to be a summarizing commentary on the arguments that happen between whites and blacks in the play. Though its many years later, the different characters are essentially arguing about similar issues at heart. For both, the contention arose solely because either side was not willing to give in based on race. The significance of this play was that it can be a commentary not just on the blackness/whiteness dichotomy in the United States. It is a problem that we face in discriminating against people on all kinds of differences, not just race.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.